Build Students’ Digital and Information Literacy with Checkology

by Kristi Reyes

by Kristi Reyes, Mira Costa College, Oceanside, CA

Posted May 2018

The amount of information online is staggering, and with one in four U.S. adults online “almost constantly” (Pew Research Center ), the ability to scrutinize online information before commenting, sharing, or acting on it is reaching a critical point. How do you evaluate the credibility and reliability of an online source? Sometimes we can just “tell” that a Web site is not authentic, but can all adult students apply the same critical eye?

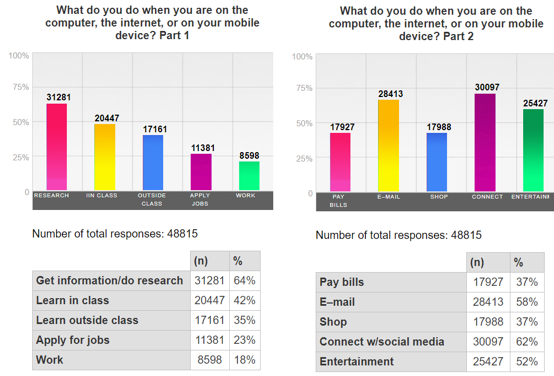

According to the 2016-17 Learner Survey Results that are part of the program and accountability requirements for WIOA-funded agencies and collected annually for each agency’s Technology Plan, of the 48,815 adult education students who took the survey, the top two internet uses reported are get information/do research (64%) and connect with social media (62%).

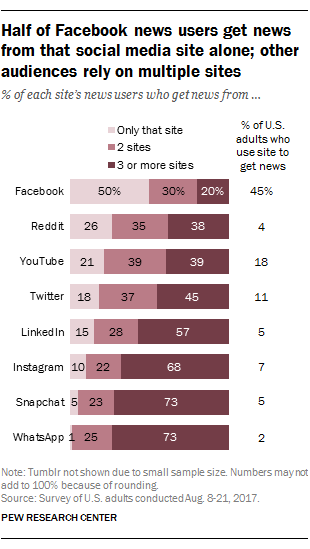

These data seem to be in line with the U.S. population in general. Furthermore, as of August 2017, two-thirds (67%) of Americans report that they get at least some of their news on social media – with two in 10 doing so often, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center , with 45% of those adults getting their news from Facebook and one or two other sites. We can surmise that our adult students similarly rely on social media as their main sources of news and information.

However, while California adult learners’ technology habits are similar to other adults throughout the United States, technology use does not necessarily equate with technology know-how. The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) developed and conducts the Survey of Adult Skills in over 40 countries. The survey measures adults’ proficiency in key information-processing skills - literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments - and gathers information and data on how adults use their skills at home, at work, and in the wider community.

According to recent figures from the survey, only 31% of the adult population in the United States score at the highest levels in problem solving in technology-rich environments, a proportion significantly below the average of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries participating in the Survey of Adult Skills . The organization’s survey data indicate that “[h]aving the highest levels of skills in problem solving using ICT (information and communication technologies) increases chances of participating in the labour force by six percentage points compared with adults who have the lowest levels of these skills, even after accounting for various other factors, such as age, gender, level of education, literacy and numeracy proficiency, and use of e-mail at home. Adults without ICT experience are less likely to participate in the labour force; if they are employed, they earn less than adults with ICT experience, after accounting for various other factors. Experience in using ICT has a particularly large impact on participation in the labour force and earnings in Australia, England/Northern Ireland (UK) and the United States. Workers who use ICT frequently have substantially higher wages than those who do not use ICT often.”

Clearly adult educators can play a positive role in developing adult students’ digital and information literacies by incorporating information and communication technologies into the instruction and learning, but it that enough? Given that so many adults in the United States get their news from social media combined with the fact that there is a growing proliferation of “fake news,” Common Sense Education’s argument for teaching information literacy (also often referred to as digital literacy or media literacy) makes more sense than ever. To better prepare students for their roles as employees, parents, and community members, adult educators need to help their students gain the following skills:

- effective techniques for evaluating the quality and credibility of websites

- critically thinking about the intentions of commercial websites and advertising

- various search strategies to increase the accuracy and relevance of online search results

Luckily more and more resources are becoming available to provide teachers with content that can be used as class assignments or supplemental/homework to help students gain these skills.

Checkology , a site from the News Literacy Project aimed at students in grades 6-12 but appropriate for use in adult classes, provides tools, tips, and resources to train students to learn how to discern fact from fiction. The site’s promotional video provides a helpful overview of the site’s 12 core lessons.

With the basic (free) account, users can access a Basic teacher guide with standards alignment and comprehensive blended e-learning strategies, including Project Based Learning and civic engagement extensions. A premium teacher account allows you to create individual logins for students, customize lessons, monitor students’ progress, and evaluate their work by providing feedback and in the virtual classroom. Students can earn points and skills badges, and they can save their work between sessions. Checkology is currently giving away free upgrades to the premium account along with student licenses for the 2017-18 school year. If, after previewing the site you find the site’s resources useful, when you register for an account, you can select “upgrade” any time through the month of June to unlock all the site’s resources.

The site’s multimedia content is delivered by journalists, constitutional law experts, and digital media specialists. The lessons use real examples of news and information with the aim to teach students how to do the following:

- Categorize information

- Make and critique news judgments

- Explore how the press and citizens can each act as watchdogs

- Detect and dissect viral rumors

- Interpret and apply the First Amendment

- Investigate the impact of personalization algorithms

- Evaluate bias and learn about confirmation bias

There are four modules with point values for each activity:

Module 1 – Filtering News and Information

Module 2 – Exercising Civic Freedoms

Module 3 – Navigating Today’s Information Landscape

Module 4 – How to Know What to Believe

Try out Module 1 yourself. These are the four lessons of this module:

- Introduction to the Checkology Virtual Classroom (for teachers who subscribe to the premium account and have students use the virtual classroom)

- Know Your Zone: Sorting Information – a series of activities that includes informational video lectures, clips from late-night talk shows and national news TV programs, as well as online news articles, editorial articles, and radio programs and podcasts, and even political cartoons interspersed with questions that ask students to identify the purpose of each (entertain, inform, persuade, propaganda, etc.)

-

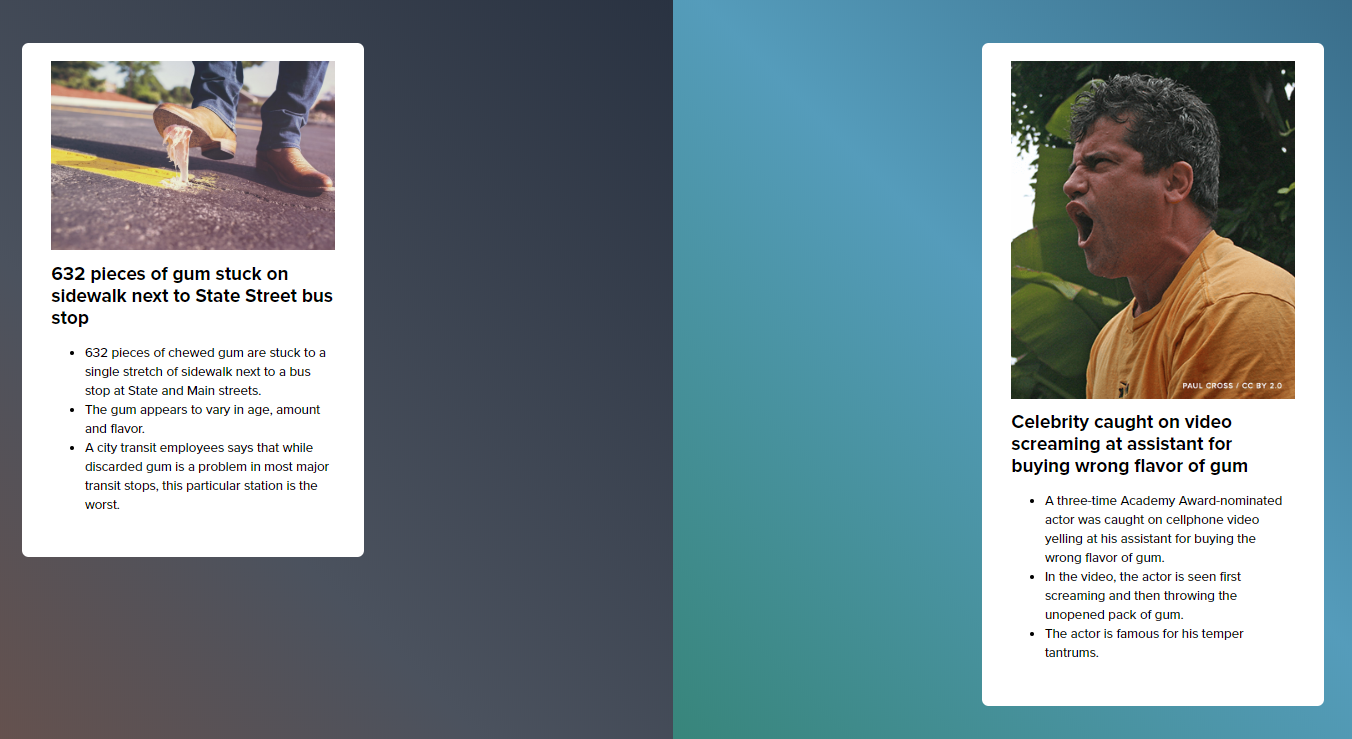

What Is News? – videos that discuss “newsworthiness” followed by questions in which users need to select the more newsworthy story followed by an explanation for each

- You Be the Editor: Deciding the Day's Top News Stories – users apply what they have learned by role-playing a newspaper editor and deciding which news stories deserve top placement on the Web site’s home page by selecting the most newsworthy and explaining the decisions of which articles to include and their positions on the home page

- Info Zone Compilation: Immigration (10 examples - a collection of authentic examples of information about immigration that were published or broadcast in 2016 and 2017)

- Info Zone Compilation: Ferguson, Missouri (15 examples to categorize)

- Info Zone Compilation: Health & Wellness (12 examples - to identify articles and images published relating to health and wellness)

- What is News? Which is More Trustworthy Part II (five more pairs of events for you to choose between based on their newsworthiness)

- News Judge: Compilation One (8 examples)

Last, a very useful tool offered on the site is the Check Tool. With it, users copy and paste in a URL for news or information found online, and the tool evaluates the credibility of the page by guiding the user through the principles taught in the modules. This could be used as a whole-class activity to introduce the concept of evaluating a source’s credibility. The tool takes the user through a series of steps and questions the user answers in order to let the user apply critical thinking to deduce the reliability of the source.

The Checkology Resources page has teacher guides, video transcripts, and module Answer Keys.

More Resources:

Common Sense Education’s Digital Citizenship Curriculum with 65 lesson plans and comprehensive learning resources for students, teachers, and family members (see Scope and Sequence for topic and Student Games and Interactives )

Finding and Evaluating Online Information: Information Fluency – September 2017 Web-based Class Activities article

Give Adult Learners the Gift of Digital Literacy – December 2016 Web-based Class Activities article

Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Everything: Critical Evaluation of Information and Information Literacy Resources

Teaching Tolerance: Evaluating Online Sources Lesson and other lessons

Extra Reading:

A Conspiracy Video Teaches Kids A Lesson About Fake News , KQED Mindshift

Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education , American Library Association

More Americans are turning to multiple social media sites for news , Pew Research Center

PIACC Gateway : research, news, and infographics on adult literacies

Social Media Use in 2018 , Pew Research Center