OTAN News

When you can’t read a medicine bottle: California immigrants struggle with low English literacy

California’s problem among the worst with 3 out of 10 adults struggling to read

“In California, an estimated 28% of adults have such poor literacy in English that they struggle to do anything more complicated than filling out a basic form or reading a short text," according to a survey from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). "California’s rate is worse than any other state except New Mexico, where the estimated rate is 29%.” These results require immediate attention and adult education has addressed this issue despite a lack of funding. This article published by EdSurge features an interactive U.S. and California map highlighting statistics by each state with a click denoting literacy statistics.

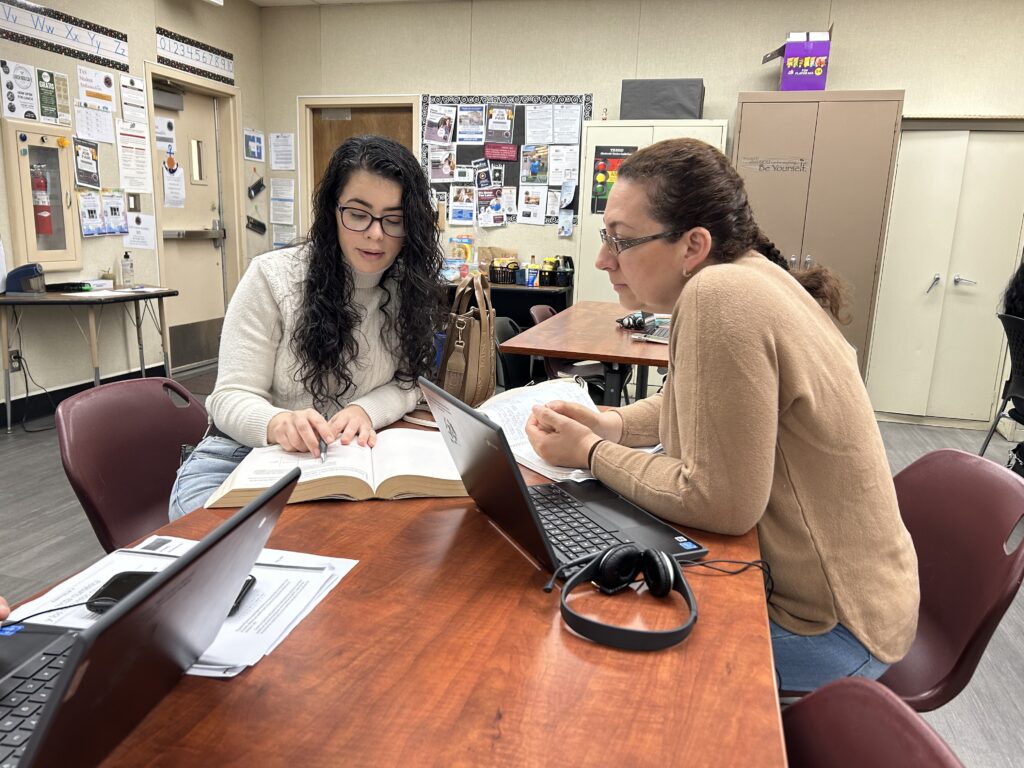

For Analilia Gutierrez, pictured with her tutor Isabel Gutierrez, the inability to read in English became not just difficult but dangerous. When her micro preemie baby needed intensive care at the time of his birth, Analilia, “who spoke and read little English,” could not keep up with the health forms and instructions for her son’s care. Even “interpreters, if available, sometimes created problems with misinterpretation.” Once her children enrolled in school, Gutierrez attended Tulare Adult School and has since “become an American citizen and earned her GED.” She said, “I would now have the knowledge [to understand], It’s so much different.”

Photo Credit: Analilia Gutierrez, left, tutors Isabel Gutierrez, right, during a Spanish GED class at Tulare Adult School. EdSource/Emma Gallegos

California is the most diverse state in the United States and “immigrants make up a huge share of workers in key industries.” The article connects an adult’s literacy skills with income, civic engagement, and health. It makes sense that low literacy is felt “not just by individuals and their families but by local and national economies. That is why researchers say adult education is a worthy investment.” “We are the best-kept secret in education,” said Carolyn Zachry, education administrator and state director of the Adult Education Office for the California Department of Education.

“Programs that serve adult students are often plagued by long wait lists, a lack of funding or a lack of accessibility. California provides robust additional funding. During the 2021–22 years, the state spent roughly $1,200 on each student who enrolled in adult education classes — primarily adult schools or community colleges. But adult educators say it is not enough to meet the great needs of its students.”

“Adult schools,” said John Werner, president-elect of the California Council for Adult Education “do it on dust. I don’t know how we pull it off.”

Adult Educators have long understood their work with adult learners is an investment not just with individual adult students but with the entire family and greater community.

“If we can pull (adult students) in,” Zachry said, “we can raise the economics of that family.”

“Werner, Director of the Sequoia Adult Education Consortium, said he’s proud of the work being done by the consortium that serves Tulare and Kings counties, which he calls the ‘Appalachia of the West.’ But he is frustrated to see that adult schools are reaching just an estimated 8% of the adults in the region who need it."

“If we could just invest in this,” Werner said. “The greatness that would come out of this.”