Sites for Developing Students’ Media Literacy and Critical Thinking Skills

by Kristi Reyes

by Kristi Reyes

MiraCosta College, Oceanside, CA

Posted January 2020

“Fake news” is an expression we didn’t use to hear every day, but it is now used by people on both sides of the political divide, sometimes to delegitimize reports that are unfavorable. The advent of fake news seems to have coincided with the 2016 presidential election, but of course it existed before then. Though not as ubiquitous these days, the National Enquirer and other tabloids with headlines such as “Bigfoot Lives!” still exist at supermarket check-out stands, but these days they tend to focus on “news” that has some connection with reality, such as celebrity gossip.

There is even a lot of news about fake news, as this variety of articles from National Public Radio shows. Some countries have made legal crackdowns on fake news, but in the United States, with first amendment rights of free speech and freedom of the press, the same governmental regulations have not been initiated.

There is so much fake news proliferating on social media, and some of it is made to look so real that even educated readers have a hard time discerning fake from real news. With another presidential election around the corner, it’s a safe bet that fake news stories will spike.

A study conducted at Stanford University found that “young and otherwise digital-savvy students can easily be duped” by what they read online. Surely the same could be true of our adult students. How can we help our students apply critical thinking skills to identify real news and distinguish it from questionable “news”?

Adult educators should infuse lessons with activities to help students develop their media literacy skills. The National Association for Media Literacy Education provides this definition as well as a broader descriptive definition: “Media literacy is the ability to ACCESS, ANALYZE, EVALUATE, CREATE, and ACT using all forms of communication. In its simplest terms, media literacy builds upon the foundation of traditional literacy and offers new forms of reading and writing.”

To become a successful student, responsible citizen, productive worker, or competent and conscientious consumer, individuals need to develop expertise with the increasingly sophisticated information and entertainment media that address us on a multi-sensory level, affecting the way we think, feel, and behave.

- National Association for Media Literacy Education

There are a few educational websites that adult educators can use in class. By visiting and spending some time on each, you will be able to see if one is more appropriate for the level of your students than the others. Checkology is one such site that was covered in the May 2018 column, “Build Students’ Digital and Information Literacy with Checkology.”

According to a recent news release from Checkology, National News Literacy Week is Jan. 27–31, 2020. The purpose is to “raise awareness of news literacy as a fundamental life skill and provide educators, students and the general public with easy-to-adopt tools and tips for becoming news-literate.”

You may want to have your students participate. The theme for each day of the week will be based on a lesson in Checkology.

- Monday, Jan. 27: Know Your Zone (“InfoZones”)

- Tuesday, Jan. 28: Standards-based Journalism (“Practicing Quality Journalism”)

- Wednesday, Jan. 29: Understanding Bias — Your Own and Others’ (“Understanding Bias”). *Note: “Understanding Bias” will be available for use in your classrooms in the coming weeks.

- Thursday, Jan. 30: A Free Press (“Democracy’s Watchdog”)

- Friday, Jan. 31: Fight Misinformation (“Misinformation”)

Here are five more websites that offer a variety of different materials for teaching digital media literacy: games, reading, videos, class activities, printable posters, and lesson plans.

The first site, Factitious, was featured in an NPR Learning and Tech story, “To Test Your Fake News Judgment, Play This Game” (with links to related articles on media literacy). Created by a journalist and originally designed for kids, the open-source game “that tests your news sense” was created in 2017. Today more than a million people have played the game.

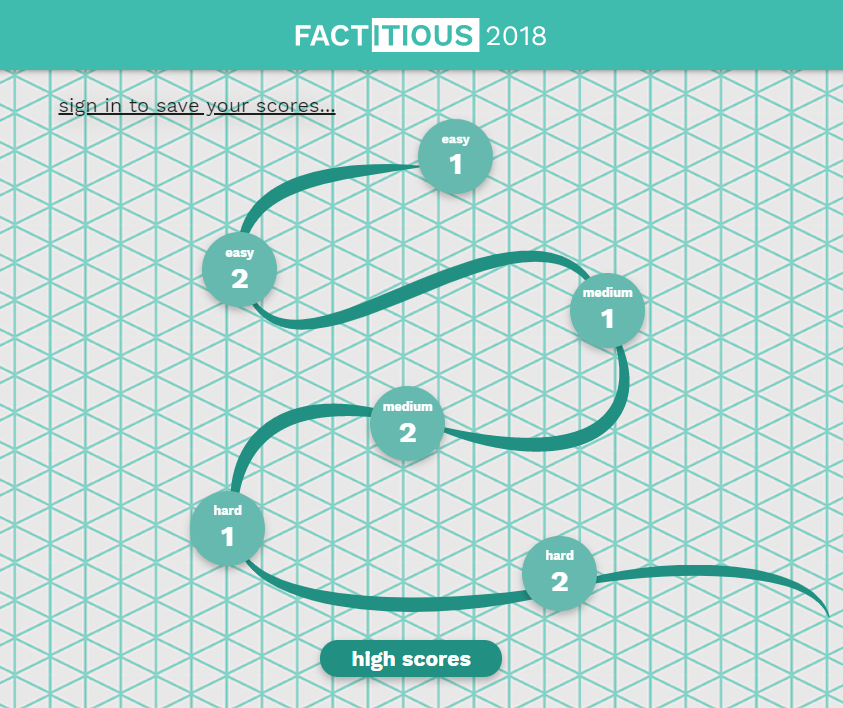

The game has six game levels, with two levels for each group: “Easy” for middle school, “Medium” for high school, and “Hard” for college. If you want to save your scores, create an account and sign in, but you can play without making an account.

Start by selecting a level in one of the three groups.

You will then see an article. If you play the game on a computer, click the checkmark if you think the article is real. Check the X mark if you think it is fake.

If you play the game on a mobile device, swipe right if you think the article is real, and swipe left if you think the article is fake. The game requires the user to read carefully because some of the articles certainly look real on the surface.

If you have trouble, you can get a clue by select “Show Source.” If a widely-known media source is provided, the article is more likely to be reliable.

Whether you select the correct answer or not, the site provides an explanation about the answer and a description about the source to help you understand better how to analyze an article for authenticity. Links to the original articles are provided for users who want to dig deeper. While you’re practicing critical analysis, you also learn the names of sources that tend to satirize, that are right- or left-leaning, or that publish humorous pieces and those that are reputable because they use rigorous fact-checking methods. When students play the game, they are learning as they go.

I played the two levels of the College – Hard game, and I did feel challenged. The articles are current and include topics in both national and world news. The two rounds took me only about 20 minutes, but it would probably take our adult students with high-school level reading ability a bit longer. The “Easy” levels do contain vocabulary that would be challenging for lower-literacy level students and some nonnative English speakers, but the articles are not necessarily kid-themed. Overall, I was engaged and learned! Wanting to play more, I visited the 2017 version of the game. The set-up is the same, so the older version can be used as a whole-class practice before assigning students to try the current version on their own.

A Medium post has this online tutorial for the game with tips, such as questions you can ask yourself as you examine a site or an online article. The “Diving Deeper” questions have the reader analyze the language used, quotations, and source. These could be the questions you use as you model an activity with any reading you bring in to your class.

The second website is GCF Learn Free.org, which has unit on Digital Media Literacy has articles in 16 sections with accompanying videos on a YouTube playlist, some of which are the following:

- Judging Online Information

- Practice Evaluating a Webpage

- What is Clickbait?

- What is Fake News?

- What is an Echo Chamber?

- Deconstructing Media Messages

- The Blur Between Facts and Opinions in the Media

Some sections of the unit guide students through a series of questions students should ask themselves when judging online information, such as questions about purpose, bias, domain, author, currency of content, checking reputation, and verifying site content with fact-checking sites such as PolitiFact.com, FactCheck.org, and the sites Snopes and Wikipedia. There are several practice activities and inclusion of real, existing websites for students to analyze.

For an assignment, you could assign a different topic to students or small groups, and they could read and watch the information, write a short summary, and present the information to the class.

Next, the website Mind Over Media: Analyzing Contemporary Propaganda helps students understand what propaganda is, how to recognize it, how to analyze its impact, and where it can be found in the Learn section. The Rate section has students apply and check their knowledge with ads, political cartoons, a video, and an infographic. Students use critical thinking to rate the source on a scale from beneficial to harmful and see how their rating compares to others who have completed the activities. The rating activities are followed by reading background information on the source, the technique used, and an explanation of why the source is considered propaganda. Users are invited to post in the discussion their interpretations of each piece of propaganda content. In the Browse section, teachers can find a wide variety of content and can filter by propaganda type. Finally in the Upload section, users can upload examples of contemporary propaganda for others to interpret and comment on it.

Because propaganda addresses all aspects of culture, MIND OVER MEDIA provides opportunities for authentic inquiry about a variety of topics, including business and the economy, health care, global issues, science and technology, politics and government, crime and law enforcement, education, the environment, and issues of faith and values.

- Mind Over Media: Analyzing Contemporary Propaganda

In the For Teachers section, there are useful resources and a link to download the entire curriculum, which consists of eight technology-integrated lesson plans, and create a customized gallery of propaganda pieces.

If you choose not to use the lessons in the curriculum but just have a brief class activity, students could be assigned to read the Learn section and view the Propaganda Techniques page, practice rating and evaluating pieces of propaganda in the Rate section, followed by students finding an ad, commercial, political cartoon, or other media and searching online for background information. Then students can introduce the content they found, analyze the content they locate to determine the propaganda type, and explain why it is propaganda to present to the class.

Next, Common Sense Education’s free Digital Citizenship Curriculum has numerous lessons that can be filtered by grade in these subject areas: Media Balance and Well-Being, Privacy and Security, Digital Footprint and Identity, Relationships and Communication, Cyberbullying, Digital Drama, and Hate Speech, and News and Media Literacy.

Within the last subject area is a media literacy lesson plan, Hoaxes and Fakes, which is written for a 9th grade audience but is appropriate for use with adults. You’ll need to sign in to see the materials. The lesson explores “Deepfakes,” which are audio or video manipulated with computer graphics and video production along with Artificial Intelligence networks re-create audio or video to realistically make it appear as though someone said something that they didn’t really say. In this Wired video, a researcher explains Deepfake videos, if you haven’t heard of these. The lesson helps instructors teach students how to check the legitimacy of suspicious online content.

The objectives of the project-based lesson are as follows. Students will be able to:

- Define "misinformation" and explore the consequences of spreading misinformation online.

- Learn how to use lateral reading (defined as “a method of determining credibility of online information in which you open multiple tabs to search for other information to validate the site’s claims”) as a strategy to verify the accuracy of information online.

- Apply lateral reading to examples of questionable videos to determine their accuracy

The 50-minute lesson includes slides, handouts, YouTube videos, quizzes, answer keys, and materials to extend the learning in families: an activity, tips, and resources. Based on the titles of videos and other content (“Pig Rescues Baby Goat” and “Nathan For You - Petting Zoo Hero”), the content steers clear of sensitive or political issues. The CrashCourse video Check Yourself with Lateral Reading: Crash Course Navigating Digital Information #3 introduces the lateral reading strategy, with students applying what they learned through analysis of other short video clips.

The lesson teaches students to search for corroborating sources as evidence that a source is true or fake and includes a teacher’s version guide. Students are encouraged to do exploring of the topic on their own by watching a TED Talk and a video about an attempt to create deepfake videos of a social media mogul and a radio talk conspiracy theorist. The lesson culminates in a project in which students synthesize and reflect by creating a video about what they have learned. The materials are also available in Spanish.

The last site is the National Association for Media Literacy Education, which has a lot of resources you can bring into your classroom, including

- A Resource Hub with reviews of media literacy education materials and several classroom activities that have been submitted by teachers

- Links to resources and lesson plans/curriculum from other websites curated in the Election/Civics Resources page of the site

- A simple visual you can download to help you explain the importance of media literacy and post in your classroom

- A useful downloadable booklet, “Building Healthy Relationships with Media: A Parent’s Guide to Media Literacy,” also in Spanish

- A Student Voice Blog provides a space for high school and university students to share how media literacy concepts and practices are informing their engagement with media culture

Students could be assigned to read other students’ post on the blog, brainstorm a list of ideas related to write their experiences with or opinions about media of all different types, write their own blog post and submit it to you for feedback, and contribute their post to the blog.

One Last Digital Media Literacy Resource for Teachers Created by a Teacher

This Google Doc for created for students is useful for teachers, too: Misleading, Clickbait-y, and Satirical “News” Sources – tips for analyzing news sources and a table that lists various online news sources and their reliability (categorized as bias, fake, satire, conspiracy, political, hate, clickbait, rumor, and even reliable). Melissa Zimdars, an assistant professor of communication and media at Merrimack College in North Andover, Massachusetts, created this resource for her university students and is referenced in article “Fake Or Real? How to Self-Check the News and Get the Facts.”